'Till We Have Built Jerusalem': The Holy City in the Imperial Imagination

One of my favourite paintings in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is Edward Lear's Jerusalem. For me, it perfectly encapsulates the nineteenth century British imagination of the ancient city, mythologised and idealised in the Christian imperial mind. Lear is symbolic of how the British viewed Jerusalem, enshrined in history, and inhabited by men barely changed since the days of the Bible.

The Ashmolean painting is the largest of five artworks of similar views of Jerusalem painted by Lear after he spent a fortnight in Palestine in 1858. It was created as a magnificent gift for his friend, Samuel Price Edwards, upon his retirement from the Liverpool customs office in 1865. The painting calls upon the imagery of the shepherds of the Gospels, with these men in traditional dress overlooking Temple Mount and the Mount of Olives; two of the most important sites in the Holy City. Such a view is breathtaking and would have been all the more fascinating for its Victorian recipient, steeped in international and religious connections.

Fifty years later, at the time of the First World War, very little had changed in the popular perception of Jerusalem. During the Palestine Offensive chaplains and soldiers alike described the Middle Eastern peoples in specific reference to scripture, as if no time at all had passed in the region in almost two millenia. Even the British press described the scene in Palestine as 'familiar to every reader of the Bible'. Moreover, the bringing of the war to this most holy of cities and its subsequent 'liberation' just before Christmas fully played into the romanticism associated with the cultural imagination of Jerusalem.

Romantic, historic and religious it may have been, but the Jerusalem imagination was also distinctly imperial. Nowhere is this more clear than in William Blake's famous poem 'And did those feet in ancient time'. His desire to build Jerusalem in 'England's green and pleasant land' was published in 1808, long pre-dating Lear, yet it did not gain real popularity until more than a century later and crucially, in the First World War. First republished in 1916 in Robert Bridges' anthology The Spirit of Man, Hubert Parry simultaneously began composing the now iconic tune, which was first performed in 1918 at a NUWSS concert.

The popularisation of Parry's rousing hymn spoke to the concept of British exceptionalism which had long connected the British Empire with the righteousness of biblical Israel. This notion was already ingrained in the elite at the time of Blake's romanticism, but was heightened throughout the imperial growth of the nineteenth century, particularly through the Victorian period, as was seen in Lear's artwork. Arguably then, this reached a culmination in late-1917 when British forces captured Jerusalem, ending its four centuries of Ottoman rule.

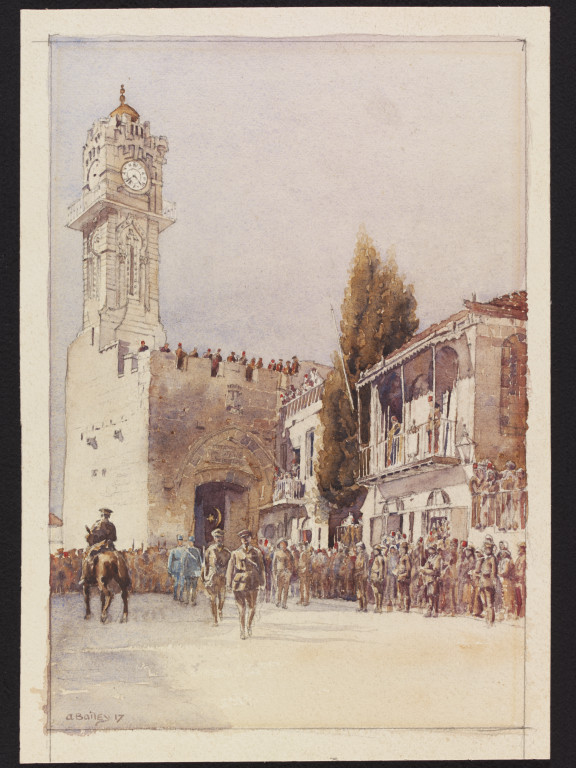

|

| General Allenby entering Jerusalem, by Alfred Bailey |

His victory was well-timed to happen two weeks before Christmas, giving ample time for the British media to become saturated with images of this as a great Christmas present for the nation, providing not only the morale boost of success, but one with inherent Christian value at a time when minds already turn to the gift and promise of that very region.

Even the language of Jerusalem was different from other wartime victories, with words like 'liberation' and 'conquest' being readily used. This was the great 'opening up' of the Holy Land, not only from the Ottoman Empire, but also into Christian influence. The subsequent British Protectorate consolidated this; the crown jewel of Jerusalem being brought into the realm of British influence. Jesus' feet may not have walked on England's 'green and pleasant land', but here were English feet definitively stamping their influence on the holy land of Israel.

For a British imperial mindest imbued with the romanticism represented by Lear, such a victory in the Holy Land was significant, serving almost as a validation for the righteousness of their cause. Although relatively insignificant to the overall outcome of the First World War, the British victory in Jerusalem provided success to the its imperial mission, bringing home this mythical distant land and fulfilling, in the name of Christianity, a perceived destiny.

Little regard, then, was given to the rupture this would cause for future generations.

Kathryn

References

Jerry Chia-Je Weng, 'William Blake and the Global Imagination'

The Times, 11/12/1917

https://www.ashmoleanprints.com/image/322348/lear-edward-jerusalem

No comments: