The World's Youngest YMCA Member

As part of the YMCA's holistic support for soldiers during the First World War, the organisation made arrangements for the loved ones of the 'dangerously wounded' to be able to visit them in the hospitals of northern France. The necessary travel permits were arranged, train and ferry crossings were organised, and often paid for, and YMCA motor cars would transport relatives to their required hospital. But most significantly, the YMCA also ran a number of hostels that could accommodate relatives during their trip, whether for a few days or even a few months.

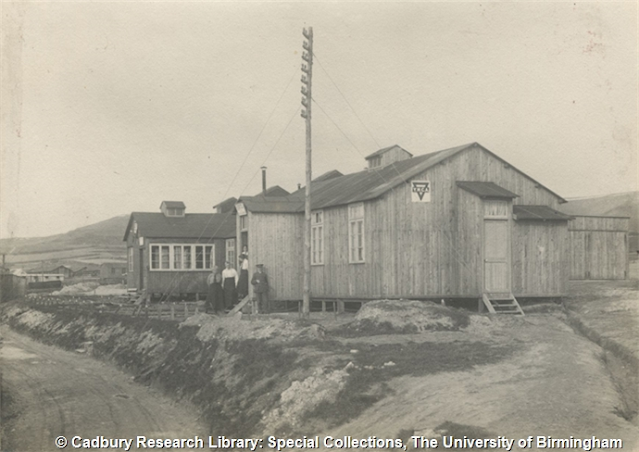

One such hostel near Camiers, on the road north of Etaples, was the Brown Hostel, named for the Brown family who donated the establishing funds. The hostel was managed by Alice Brown, of the family, who would go on to receive an OBE in recognition for her war work. She was supported by her sister, Maud Ballantyne, and Maud's 19 year old daughter Dorothy, who did some of the driving, as well as Emily Huntley who would go on to publish a short book about her time at the Brown Hostel.

The hostel opened on (coincidentally) the 14th February 1916 and within its first 10 months of operation more than 1,200 people had stayed with them, often wives and mothers, although fathers would also make the journey fairly frequently. It was prefabricated and small, with only 20 able to stay at one time, but Brown and her ladies nonetheless made every provision for their guests, from a warm bed to home-cooked food and books and games for the evenings. Huntley described the good camaraderie of the hostel visitors, how they would all muck in to help wash up or to make small entertainment for the evenings, all the while sharing the most difficult of experiences.

The men for whose families were permitted to make the trip across the Channel were in grave situations and not expected to make a recovery. For some families they arrived too late, their sons and husbands already succumbing to their injuries while they made the sometimes lengthy journey to reach them. For those people, the YMCA would help them make the arrangements with the Army authorities for a funeral or to visit their graves. But for other soldiers, a visit from their dearest wife or beloved parents was a miraculous medicine that could sometimes change their fate. Huntley described this as 'that mystic medicine which only mothers know'.

With all the horror stories about the Western Front that swirled around Britain during the war, it is impossible to imagine the trepidation with which the families, often women travelling alone, would have embarked on their sailings. Huntley posited that 'perhaps it is the arrival in France that makes the deepest impression on the travellers. Those first moments are packed with thrill that is half-fear.' They knew not what to expect, and least of all what state they would find their loved ones lying in.

For some, the journeys were particularly long. Some made spur of the moment crossings from Dublin, taking trains across Britain until they reached London from where they could make contact with representatives of the Salvation Army who would find someone to put them up before they could go on to France with the YMCA's support. Stories also abound of Australian and New Zealand family members staying at the Brown Hostel, although it seems unlikely that many at all would have been able or permitted to make such a long sailing to Europe.

Amid all the desperation which would have been ever-present in the hostel, there is one story of great light. A young lady came to stay in Spring 1917, following her husband's wounding in the Arras area. She was heavily pregnant but felt she must make the journey despite the risks. Not long after her arrival, in the middle of the night, she went into labour and gave birth at the hostel to a healthy baby boy. When she got to see her husband, it was with their son in her arms, which must have made the most profound impression upon him.

The lady, who is unnamed in all the accounts of the story I have read, remained at Brown Hostel for six weeks, while her husband recovered. All the necessary baby items were purchased locally with the YMCA women's help, and a vegetable box was made into his crib. Each day the new mother would visit the hospital and all the soldiers delighted in having cuddles with the young boy, brightening their long and painful days. Huntley wrote of how lovely it was to have the baby with them in the evenings and that they didn't mind the noise he made during the nights as he was the most positive distraction from the war.

Before they departed France, the hospital chaplain arranged a Christening for the baby so that his father could be present, a gown being bought for him from a local lady. It was recorded that as many soldiers as could made the effort to attend the service, including the officers, as well as everyone from the YMCA, in part to give thanks for the joy he had given their lives.

It can't have been easy for the new mother to have given birth under such conditions or stress about her husband's condition, but on the other hand it is remarkable how beneficial the little baby was to the injured soldiers' wellbeing and morale. Some joy and comfort, a welcome distraction, and symbol of optimism for the future, he couldn't have known how important his service was as the world's youngest YMCA member.

Kathryn

http://www.idaillinois.org/digital/collection/isl8/id/349

https://calmview.bham.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=XYMCA%2fK%2f8%2f1%2f163&pos=5

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205379993

http://scottishindependenthostels.blogspot.com/2018/11/a-very-different-hostel-1916-1918.html

No comments: