Ultimate Sacrifice: the Crucifixion and the First World War

On Good Friday, Christians across the world and throughout

history remember one of Jesus Christ’s most pivotal acts; his crucifixion.

Hanged from the cross between two prisoners, He sacrificed his life for that of

humanity. He fulfilled his promise, the New Covenant, to forgive sin and offer

salvation for all.

It is upon this sacrifice that He bore the sins of the world

and for which He is remembered as mankind’s saviour. The image of the Cross,

the Calvary, the Crucifix became Christianity’s most pertinent symbol.

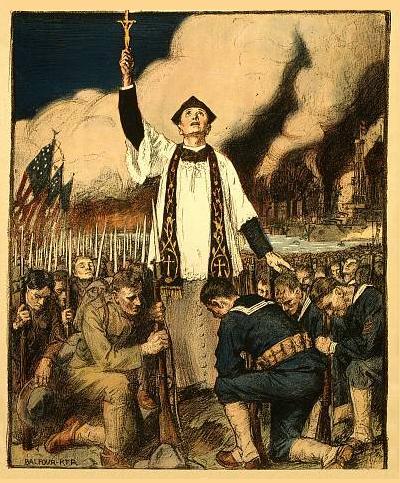

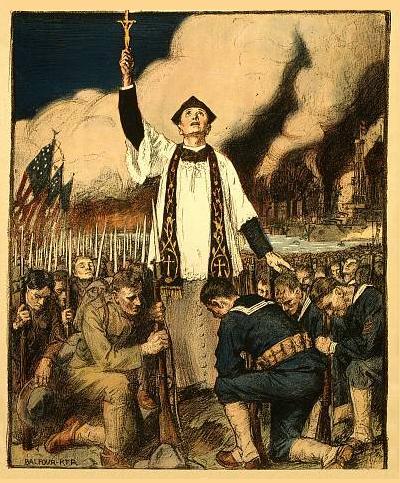

While this is true throughout Christian history, the

Crucifixion took a particularly prominent role in the ministry of the First

World War. It is not difficult to see why. The concepts of pain and sacrifice

resonated with soldiers, and the teachings of God’s Plan and salvation were

employed as succour for those desperate for answers and reason in conflict.

At its simplest, this can be seen in the widespread

popularity of Isaac Watts’ hymn ‘When I Survey the Wondrous Cross’ in wartime

services. In my entirely anecdotal survey of such services, chaplains’ recounts

and hymnals, this is the most popular hymn, perhaps second only to the National

Anthem. The lyrics recount Jesus’ sacrifice, of the ‘sorrow and love’ of the

act of Crucifixion. Sung in the circumstances of war, whether in a bombed out

church or a YMCA hut, it is difficult to imagine someone not to be moved by the

final two lines of ‘Love so amazing, so Divine/ Demands my soul, my life, my

all’, which appealed to the soldiers’ sense of duty and responsibility.

The ‘Wondrous Cross’ intrinsically linked the duty and

responsibility of the soldier with that of Jesus, creating a sentiment of

kinship. This method was particularly employed in the ministry of the YMCA,

with General Secretary Arthur Keysall Yapp presenting Jesus deliberately as that

‘Friend’ – Jesus Christ – ‘who will never fail him nor forsake him’. Here, Yapp

is quoting Moses telling Joshua to ‘Be strong and of a good courage, fear not,

nor be afraid of them: for the Lord thy God, he it is that doth go

with thee; he will not fail thee, nor forsake thee.’ However, he manipulates

the sentiment to apply directly to Jesus: the human face of God.

If God was to be the ‘Friend’ who stood by and guided a

soldier in the trenches, the easiest presentation of this was through the face

of Jesus, especially given the low levels of religious education with which

chaplains had to work. Jesus could be visualised, his stories shared, and a

spiritual relationship developed. Given the pain, loss and sacrifice of

wartime, the Passion of Christ became a recurring motif. Chaplains had to

confront issues of death and theodicy, and these conundrums had to be answered

without complex theological arguments. Moreover, this was important not only

for maintaining the soldiers’ connection with Christianity, but also for the

benefit of their morale and to avoid the dreaded undercurrents of fatalism.

William Soothill, a Christian writer during the war,

identified that the preoccupation with the Crucifixion was because soldiers

were ‘facing Death and they know it’, and thus easily connected with the

situation of Jesus’ death on the Cross. The connection is clear. Jesus is shown

as the Personal God, exposed on the Cross in his human body, unable to avoid

pain and death for the benefit of mankind. AH Gray connected the two

experiences in a theological pamphlet, describing them as examples of

‘perpetual endurance’. One side of this was a shared sacrifice, but

the other was the need for ‘quiet strength’ and ‘consummate bravery’, by both

Jesus and the soldiers, amid the strain and suffering of conflict, or life’s

‘burden’ as Gray described it.

At the ninth hour, Jesus also makes a very human

exclamation. ‘My God, My God, why have

you forsaken me?’ (at least in the reporting of the Gospels) would certainly

have resonated with those suffering in the First World War. While there is no

great trend of soldiers losing their faith between 1914 and 1918, many

certainly questioned their faith in times of pain. For Jesus to have done the

same, further creates kinship between the two experiences, as well as

reassurance to the Christian soldier that they were allowed to question and

doubt their belief. For the Christian knows that Jesus was not forsaken, and

thanks to His sacrifice, neither will the believer.

Connotations of the Crucifixion were also employed on a more

abstract and longer lasting level. The use of the term ‘Ultimate Sacrifice’ in

reference to military death draws an automatic comparison to the ultimate

sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross to anyone religiously minded. Of course, the

death of the soldier for King and Country is not coequal to the Sacrifice of

Jesus, yet similar linguistic tools are employed. Perhaps this points to our

reliance on the Biblical language to explain and understand our lives, but it

also suggests an imposed significance and sacrility on the deaths of soldiers

in the First World War.

While discussion of Crucifixion was an important feature of

wartime ministry, particularly that aimed at the layman without a complex

biblical understanding, some theological scholars believed the act of war

itself indicated a lost connection with the true meaning of Jesus’ life. One such writer, John Proctor, in a pamphlet

written for clergy working with the YMCA, observed that ‘the need for

the Sacrifice of Christ is abundantly demonstrated’ amid the sin of war. He highlighted

the presentation of the crucifixion as Jesus ‘who was delivered for our

offences’, in a quotation from Romans. It was this sacrifice for our sins,

which Proctor considered to have reinvigorated pertinence in the context of war

which was ‘revealed in all its native ugliness as an exceedingly hateful

thing’, in much the same way as Pilate’s murder of the innocent Jesus.

It is certainly difficult to argue that Jesus absolved the world of sin,

given the acts of evil across the battlefield.

However, Proctor is less convincing when he says that ‘such

appeals’ about Jesus’ atoning death were ‘all too rarely made by those in touch

with our brave fellows’ and encouraged further preaching and education about

the crucifixion through the YMCA. As discussed above, chaplains and clergy in

touch with the active fronts made continual reference to Jesus’ death and

sacrifice, albeit often limited by the understanding of their audience.

Nonetheless, despite his negativity, Proctor’s pamphlet reinforces the significance

of the Crucifixion narrative in the understanding of experiences of war in the

early Twentieth Century.

Some clergy, such as Reverend James O Hannay, believed that men

were ‘learning the meaning of the Cross of Christ’ as a direct result of the

war, as per his analysis of wartime preaching published in 1917. This suggests

that, at least to some extent, Proctor’s plea was being put into action (inadvertently

or otherwise). As I have discussed above, this certainly seems to have been the

case. The singing of Jesus’ ‘love so divine’ that he gave his life, in a

sacrifice for the benefit of humanity, definitely carries many salient points

for the soldiers of the First World War. Understanding may not have been

thorough, many men may not have been aware of Jesus’ personal doubt, yet the

basic concepts of the selfless death and the confrontation of fear would have

been all too common for those fighting on the front line.

What is striking is that for all the talk of the Crucifixion

during the First World War, comparatively little – if any – attention is paid

to the Resurrection. I cannot pretend to have the answers for this and it is an

area of personal interest. Good Friday does not stand alone, but gains its

significance from Easter Sunday, when Jesus overcame death and proved himself

as the Son of God. One indication of why this could be lies in the emphasis

placed on Jesus as the Personal God, with a physical body, in presentations of

the Crucifixion. Servicemen felt kinship to this God, to Christ who had to face

death as they did, but who did so for all humanity. Such empathy would have

been more difficult to connect with the resurrected Spirit, who overcame death.

However, it is in the Resurrection that Jesus demonstrated

his power. He was the son of God who conquered the great evil of death. There

are certainly many references made to Heaven during the First World War, most

notably in the epitaphs of the fallen. However, such a connection and

celebration that ‘He is Risen!’ does not feature anywhere near as often in the

writings of clergymen, or the recordings of services and sermons from the War.

I am more than willing to be proved wrong on this. Discussion of the resurrection and what it meant for Christian society at war almost certainly would have been ongoing during the First World War, whether merely between clergy or with the soldiers themselves. However, with the pressures of warfare and the varying levels of religious education among both soldiers and non-combatants, it makes sense the it was to the message of Good Friday that Christian teaching during the First World War so regularly returned. After all, it is the Cross which is the symbol of the Christian faith, and which potently marked so many graves of those men who had paid their Ultimate Sacrifice in war.

Kathryn

Kathryn

No comments: