Geoffrey Malins and the Battle to Film the Somme

Just before Zero Hour on 1st July 1916, thousands of soldiers stood in wait, ready to go over the top in the much-anticipated Big Push. They fixed their bayonets and readied their rifles, awaiting the sound of the whistle to signal them forward.

Yet in the line behind the Hawthorn Ridge stood a man armed for very different shots. Lieut Geoffrey Malins was waiting with his film camera, about to capture the iconic footage that would shape the way Britain has seen the Battle of the Somme ever since.

Documentary footage of war had been around since 1898 when clips of soldiers at the Spanish-American War were recorded. Shortly after, footage was broadcast of soldiers preparing for the Battle of Omdurman, yet it wasn't until the First World War that actual battle scenes were videoed. At the outbreak of war in 1914 moving pictures had been recorded for just over twenty years and the cinema was already establishing itself in the cultural fabric. By 1916 there were 4,500 cinemas across Britain, showing a range of news reels and entertainment films.

Malins certainly enjoyed the adventure of his work, a roving "movie man" who was given the freedom to go where liked behind the lines of the Western Front. His memoir records many near misses, where a bullet whistled past him or he was covered in the mud of a shell exploding nearby. Much of this is almost certainly dramatised, unsurprisingly for a man with a gift for telling a story.

The time Malins spent at the front was always split into short bursts, between which he would travel tack to London, personally couriering his films to be made into newsreels. As crossing the channel became more dangerous, Malins would seal the film canisters shut with a rubber glue and tie them to his body with rope to protect them in case of the ship's sinking.

The War Office soon responded to this new opportunity of bringing the footage of war to audiences on the home front and in March 1915 Malins was hired alongside Edward Tong as official cameramen to the British Expeditionary Force. They were both given the rank of Lieutenant. Tong would soon be invalided home, but Malins continued to travel around the front, filming the British soldiers in the Ypres Salient, at Neuve Chapelle and in Arras throughout late 1915 and the first half of 1916.

By now, Malins was well experienced in the challenges of film-making on the battlefield. Accompanied by assistants he would lug his tripod and heavy cameras in and out of the trenches, his replacement reels strapped under his coat. When filming into No Man's Land he would often have to camouflage his camera as much as possible, aware that it was an obvious target for enemy snipers.

By now, Malins was well experienced in the challenges of film-making on the battlefield. Accompanied by assistants he would lug his tripod and heavy cameras in and out of the trenches, his replacement reels strapped under his coat. When filming into No Man's Land he would often have to camouflage his camera as much as possible, aware that it was an obvious target for enemy snipers.In anticipation of the Battle of the Somme the wounded Tong was replaced by John McDowell as the second official cinematographer. Interestingly, Malins doesn't mention either man in his memoir, writing very much in the singular of his efforts to film the war. Certainly, the men worked separately in France - McDowell would be in Mametz on 1st July - yet they were both there for the same purpose and worked in co-operation to create the newsreels. McDowell's contribution is definitely worth bearing in mind when considering Malins' role in shaping the national memory of the Somme.

As the battle neared, Malins moved to the Beaumont-Hamel in order to scout locations for the Big Push. As the bombardment progressed, these sites were fast-changing; every day seemingly suitable positions would be destroyed or exposed.

His first location on the morning of 1st July was in the now-famous Sunken Lane in which the 1st Bn Lancashire Fusiliers sheltered beyond the front line trenches awaiting the attack. It was reached through a small tunnel dug out from the trench line, through which Malins struggled to carry his camera equipment. He later recalled how 'it was difficult to imagine we were midway between the Hun lines and our own. It was practically inconceivable. The shell-fire seemed just as bad as ever behind the trenches, but her it was simply heavenly'. They were protected by the steep banks of the lane.

It was here that some of Malins' most iconic footage was shot of the waiting Fusiliers. 'Some of them looked happy and gay', he recalled, while 'others sat with stern, set faces, realising the great task in front of them'. These faces have been analysed numerous times since as people have sought to identify their ancestors or to lip-read what they might have been saying. In one documentary with Andrew Robertshaw, a forensic lip-reader identified one man as saying 'I hope we're not in the wrong place'.

It was one of Malins' biggest regrets that his footage was silent. He worried that the audience watching it, 'comfortably seated in the picture theatre', would be missing out on a big part of the experience, unable to grasp the terror without the sound of shells. I think for modern audiences, so used to video with sound, this is exacerbated. The footage of the lane appears peaceful, a small group of men in the calm before the storm, no sign of the bombardment or the hundreds of men continuing to arrive. Those who have seen Peter Jackson's recently restored version of this footage in 'They Shall Not Grow Old' will understand the difference of what could have been, should the technology have allowed.

At Malins' next location sound is arguably even more crucial to the experience. The scale of the explosion of the Hawthorn Ridge mine is inconceivable; the size of the explosion must have been truly deafening. Such an explosion also presented an immense challenge to Malins to film. The length of exposure on his camera was limited and he had to time it correctly. This was arguably the biggest moment of his career and one of international importance at that.

'The horrible thought flashed through my mind, that my film might run out before the mine blew ... The agony was awful; indescribable. My hand began to shake. Another 250 feet exposed. I had to keep on. - Then it happened. - The ground where I stood gave way to a mighty convulsion. It rocked and swayed. I gripped hold of my tripod to steady myself. Then, for all the world like a gigantic sponge, the earth rose in the air to the height of hundreds of feet.'

He returned to London a few days later when work quickly began on the 'Battle of the Somme' film. Initially, McDowell and Malins were capturing footage for the purpose of the newsreels, yet the power of the images were quickly realised and the 77-minute film of the battle was instead created by the War Office, the narrative fleshed out with reconstructed scenes where live filming had not been possible. Like the work of his colleague, these reconstructions are not mentioned in Malins' memoirs and the film is presented without drawing attention to this fact. The film was an important piece of propaganda, showing the home front their brave loved ones at war.

There had been concern, shared by Malins, that the presentation of death in the film, in which soldiers are seen being mowed down as they go over the top of the trenches [in possibly reconstructed shots]. Yet, the public were clearly aware of the scale of death in the battle, as reported in both local and national newspapers, and Malins argued that the killing presented in the film was 'only a very mild touch of what is happening day after day' in the war.

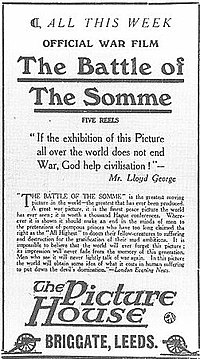

The film, upon its release in August 1916, was an immediate success. Twenty million tickets were sold for the film in its first six weeks and there are reports of some people returning to watch it numerous times.

The film, upon its release in August 1916, was an immediate success. Twenty million tickets were sold for the film in its first six weeks and there are reports of some people returning to watch it numerous times.In the century since the war, the 'Battle of the Somme' has not lost its significance. In 2006 it was entered into UNESCO's 'Memory of the World Register'. Clips from the film have been repeatedly used to illustrate documentaries, its scenes becoming important tools in the teaching of the First World War. The stories, particularly those captured by Malins, of the First Day of the Somme have informed and shaped cultural memory of the battle ever since.

The emphasis on Malins' footage over McDowell's in this role is multi-layered. Firstly, Malins was filming with 29th Division on a section of the front which suffered some of the worst losses. Almost 500 men of the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers, who Malins had filmed that morning, were casualties by lunchtime. His footage fitted the dominant narrative that emerged of a day of tremendous loss. Meanwhile, McDowell filmed at Mametz, one of the few successes for the British on that first day. Moreover, as Nicholas Hiley has identified, the film's producers deemed McDowell's attack footage 'unusable', meaning that the resulting film was weighted towards the images shot by Malins. I do also wonder how much Malins' celebrity was later compounded by his memoir, 'How I Filmed the War', which is very individualistic and makes no mention of other contributions.

By the time 'The Battle of the Somme' was released, Malins was back in France, continuing to film for the newsreels. He spent much of the rest of 1916 on the Somme, filming the later stages of the battle. He missed much of 1917 due to sick leave but was able to return to film the Battle of St Quentin in 1918 before being invalided out of the Army. After the war he returned to commercial film making and eventually retired to South Africa, where he died in 1940.

Kathryn

Geoffrey Malins' memoir, 'How I Filmed the War' can be read online here.

The 'Battle of the Somme' film can be watched online here.

Other sources:

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/geoffrey-malins-and-the-battle-of-the-somme-film

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/the_battle_of_the_somme_film

http://www.webmatters.net/txtpat/index.php?id=61

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteGreat Information sharing .. I am very happy to read this article .. thanks for giving us go through info.Fantastic nice. I appreciate this post. https://primewire.today

ReplyDeleteVery nice article, I enjoyed reading your post, very nice share, I want to twit this to my followers. Thanks!. https://primewire-movies.com

ReplyDeleteThis article was written by a real thinking writer. I agree many of the with the solid points made by the writer. I’ll be back. https://putlocker.quest

ReplyDeleteGenerally, common surfers don't have a clue about how to watch movies online. مشاهدة افلام اون لاين مباشرة

ReplyDeleteI think this is an informative post and it is very beneficial and knowledgeable. Therefore, I would like to thank you for the endeavors that you have made in writing this article. All the content is absolutely well-researched. Thanks... https://putlocker.work

ReplyDeleteHii,

ReplyDeleteThis is great and awsome post for me. i loved to read your blog. it's really-really amazing. thanks for inspired me by your blog.CapitalGrocery

Fortune Soya Health

Fortune Sunlite Refined

Fortune Soya

MDH Deggi Red Chilli

MDH Biryani Masala

MDH Jaljeera Masala

Rajma Masala (100 gm)

very interesting keep posting. https://123putlocker.website

ReplyDeletesd

ReplyDeleteThe world would indeed be a nicer place if people we didn't even know were willing to spend all of that money so we could download free online movies, TV shows and more. 5movierulz Bollywood

ReplyDeleteLinora Store Discover Linora Store – Dubai's destination for luxury furniture, modern home decor, and elegant arts. Explore timeless designs and transform your living.

ReplyDeletefossil fuels, reduce their reliance on the US dollar, and streamline banking and cross-border transactions.

ReplyDelete불밤출장아로마

휴미출장아로마

쩜칠출장아로마

프리덤출장아로마

불밤출장아로마

궁합출장아로마

샤쿠미출장아로마

토끼출장아로마

샤쿠미출장아로마

달새출장아로마

مشاهدة وتحميل فيلم ومسلسل اون لاين

ReplyDeleteمن الصفحة الرئيسية لموقع سيما لينا يمكنك مشاهدة الافلام والمسلسلات بسهولة.

مشاهدة فيلم ومسلسل اون لاين مباشرة

تحميل ومشاهدة الافلام والمسلسلات بدون اعلانات.

مشاهدة فيلم ومسلسل وتحميل مباشر

موقع ToCima لمشاهدة الافلام والمسلسلات الجديدة من الصفحة الرئيسية.

مشاهدة فيلم ومسلسل مباشر

صفحة المشاهدة الرسمية لموقع تو سينما.

مشاهدة وتحميل فيلم ومسلسل اون لاين

Cima2Day يوفر مشاهدة الافلام والمسلسلات اون لاين بسهولة.

مشاهدة فيلم ومسلسل اون لاين

تحميل مباشر ومشاهدة بجودة عالية.