The Way of Peace They Have Not Known: The Peace Programme of the YMCA

This week marks 100 years since the celebration across Britain of 'Peace Day', the Bank Holiday to celebrate the end of the First World War and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. A Victory Parade in central London was the main focus of the national celebrations, ending at the unveiling of the then-temporary Cenotaph on Whitehall.

In their monthly journal, the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) hailed this day as 'the greatest occasion for thanksgiving the world has ever known', praising God for the end of the war. The editorial went on to describe how 'like hounds straining at the leash, we are eager to get on with some of the fascinating problems of reconstruction that confront the YMCA'. Buoyed by the unprecedented success of their war work, they were keen to take advantage of the 'supreme opportunity' given to them by the war by further developing their work in the new post-war world.

Having been considered by many soldiers to have been a 'ubiquitous feature' of their war service, the Association sought to establish an ongoing programme to similarly support the veteran, continuing to provide the men with recreation, education and spiritual support after demobilisation. In July 1919, the same month as Peace Day was celebrated, the YMCA laid out its 'immediate programme' for the ex-soldier and sailor, consisting of a four strand approach. These were:

- The finding of employment for ex-service men

- The provision of manual training

- The establishment of hostels and recreation centres for discharged men

- The creation of outdoor training centres

This was an ambitious strategy, designed both to reintegrate the men into civilian life and employment, and to continue to provide them with a space for homosocial bonding, similar to that of the wartime recreation huts.

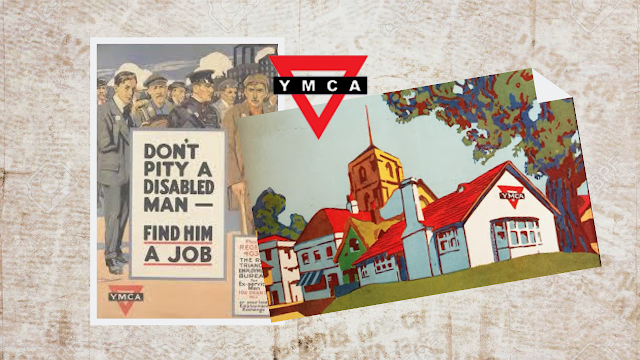

In the history of the YMCA the first section of the programme is perhaps the most significant. Between 1916 and 1927 the Association found employment for more than 36,000 men from their London office, run under the guidance of Mr T.E. Fulcher. Benefitting from free advertising in a number of national newspapers, the YMCA's Employment Bureau was able to help ex-service men, including a large proportion of wounded soldiers, to find suitable jobs. Such positions ranged from low-paid domestic work to secretary roles at more than £300 salary. This work was a significant contribution to the lives of many men re-adjusting to life after the war.

Sections two and four of the programme can be looked at together, for they both ambitiously set out to improve the health and well-being of men. Manual training was centred on the country's major urban areas and the outdoor facilities were set up in Dorset, Surrey and Suffolk, both seeking to provide opportunities to working class men. At Kinson in Dorset a YMCA farm was established for the benefit of ex-soldiers suffering from tuberculosis, a specific example of the Association's work to support vulnerable men after the war. However, funding for this project soon ran out and the farm closed. Like many of the YMCA's training facilities it was unsustainable, seemingly unsupported and unable to operate in the difficult conditions of the 1920s.

Finally, the YMCA sought in its Peace Programme to continue its project of recreation centres, moving them from the active fronts of the war onto every village green in Britain. Redesigned as 'Red Triangle Clubs' they endeavoured to provide a space for young men to spend their free time away from the perceived 'immoral' space of the pub. The excitement with which the Association introduced this new work can be seen in the fact that the coloured drawing of the ideal village hut was the first full-colour front cover of The Red Triangle Monthly, appearing in August 1919. This was in every way seen to be the YMCA's bright new future.

As of 1924, there were almost 300 such clubs across the country, seen to be operating as complementary establishments to the new Women's Institute. However, the programme never reached the heights envisioned by the YMCA's central committee and didn't reach the same national precedence as the WI.

The momentum with which the Association carried from the Armistice soon began to wane and attention soon shifted away from their work. The YMCA was significantly overdrawn, having to almost halve its annual budget in 1920 as their wartime fundraising began to dry up and their work was too overstretched to make a profit. The General Secretary, Sir Arthur Keysall Yapp, was forced to declare that 'economy must be our watchword'. Consolidation soon replaced their mission of expansion.

It is striking just how rapidly the Peace Programme was determined to be unviable and began to be phased out. Within three years of the Armistice some of the YMCA's major hostels and centres in London were being closed as they were no longer receiving the levels of support they had enjoyed during the war. No clear reason is given for this failure. Elsewhere, associational membership was thriving. It could be suggested that growing secularisation turned men away from the YMCA as a religious organisation, yet with the successful establishment of Christian organisations such as Toc H after the war, this does not seem like it is the sole explanation.

I would instead contend that the YMCA struggled in the transition to peace because it no longer had the clear mission of its war work, and was fighting for relevance in a far more competitive market than the one it had dominated during the war. For some men, its very connection and reminder of the war would have been uncomfortable in their effort to rediscover normality. Just because something thrived in the culture of war did not mean that this would carry forwards into peace and, as the YMCA quickly discovered, these trends could shift rapidly in the disrupture of the early 1920s.

Kathryn

Quotations in this article have been taken from The Red Triangle, the YMCA's monthly journal. It is based on a conference paper I gave last week from research for my DPhil study.

No comments: